Communicating with Music: Mouth Music, Bugle Calls, and Fanfares

It is often said that music is a language. In many cases the meaning of a musical language is vague and emotion. But the examples from this section demonstrate that music can quite literally and be used as a language conveying specific and pertinent meaning.

Mouth Music

There are various theories regarding the relationship of language to music. One idea posits that language emerged from human use of survival calls (not unlike bird calls). Calls are used keep track of group members, to warn if impending danger, or to attract the opposite sex. In the following video clip, several of the examples of “mouth music” have specific and well understood functions. In some cases, language is turned musical, in others musical sounds suggest a message. Hollering, for example…

is considered by some to be the earliest form of communication between humans. It is a traditional form of communication used in rural areas before the days of telecommunications to convey long-distance messages. Evidence of hollerin', or derivations thereof such as yodeling or hunting cries, exists worldwide among many early peoples and is still be practiced in certain societies of the modern world. In one form or another, the holler has been found to exist in Europe, Africa and Asia as well as the US. Each culture used or uses hollers differently, although almost all cultures have specific hollers meant to convey warning or distress. Otherwise hollers exist for virtually any communicative purpose imaginable -- greetings, general information, pleasure, work, etc. The hollers featured at the National Hollerin' Contest typically fall into one of four categories: distress, functional, communicative or pleasure (Folkstreams.net “Welcome to Spiveys Corner: The National Hollering Contest” http://www.folkstreams.net/film,238 (accessed 24 January 2014).

Viewing: Dunlap, B. & S. Korine (1981) Mouth Music (4:00 – 12:00) http://www.folkstreams.net/film,173 (accessed 24 January 2014).

Bugle Calls

Bugle calls are musical signals that announce scheduled and certain non-scheduled events on an Army installation. Scheduled bugle calls are prescribed by the commander and normally follow the sequence shown below. Non-scheduled bugle calls are sounded by the direction of the commander. (On Music Dictionary “Daily Sequence of Bugle Calls” http://dictionary.onmusic.org accessed 24 January 2013)

Viewing: Taps, the Bugler’s Call – The Origin of Sounding Taps http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nhtr5J00ntA (accessed 24 January 2014)

Daily Sequence of Bugle Calls (From On Music Dictionary “Daily Sequence of Bugle Calls” http://dictionary.onmusic.org (accessed 24 January 2014))

First Call

Reveille

Assembly

Mess Call (morning)

Sick Call*

Drill Call*

Assembly

First Sergeant’s Call*

Officer’s Call*

Recall*

Mail Call

Mess Call (noon)

Drill Call*

Assembly

Recall*

Listening: You Tube. “Bugle Calls of the U.S. Army” Played by W.G. Johnston Culver Military Academy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4tliFA3MmA (accessed 24 January 2014).

Fanfares

A fanfare is a brief musical composition for brass instruments and often percussion, used to announce the beginning of important ceremonial events, or to imply importance (as in the use of fanfares at the openings of film and theatrical productions). Fanfares rely heavily on the harmonic series and feature dotted rhythms and repeated patterns. Fanfares differ from bugler calls in that they are not tied to a single harmonic series, tend to be longer, and are not used to convey specific messages or instructions. Fanfares developed from improvisations based on bugler calls.

Fanfare Examples

“Royal Entrance Fanfare”

Lemmens, Nicholas “Fanfare”

Britten, Benjamin “Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury”

“Victory Fanfare” from Final Fantasy VII

“Boss Clear Fanfare” from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker Soundtrack.

Chaplin, Charlie “Circus Fanfare” excerpt (0:20 – 0:30) and “A Magician Exposed” from the film The Circus (1928), including CBS logo music (0:00 – 0:18)

Universal Logo 100th Anniversary

Williams, John (1984) Olympic Fanfare and Theme

“Fanfare: Arranging a Fanfare”

Functions of the Fanfare

Fanfares are often used for the following;

- For ceremonial occasions to draw attention to an important announcement.

- To announce the start or close of an important event

- To announce the start of a horse race, and some other sporting events

- To send messages across large open spaces, especially in battle (pre-WWII)

- To announce the arrival of an important figure

- To honour service men and women killed in action

- To direct hounds in a hunt (hunting horn)

Fanfare Style (Musical Conventions):

- Relatively short in duration (common)

- Loud (not always)

- Traditionally, uses notes of the harmonic series (common, though the fundamental may shift)

- Contrast of melodic leaps in the lower register with stepwise movement in the higher register (common, as this is a natural property of the harmonic series)

- Scored for or performed by brass with or without percussion (common)

- Strong rhythmic character often using repeated rhythms (semi-quavers, dotted rhythms and triplets) and repeated notes at the same pitch (common)

- Use of imitation within and between parts (common)

- Contrast imitatative, contrapuntal textures with rhythmic chordal passages (sometimes)

- Use of short phrases (2-6 notes)

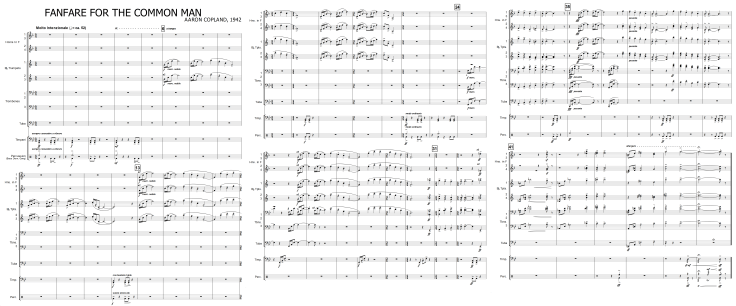

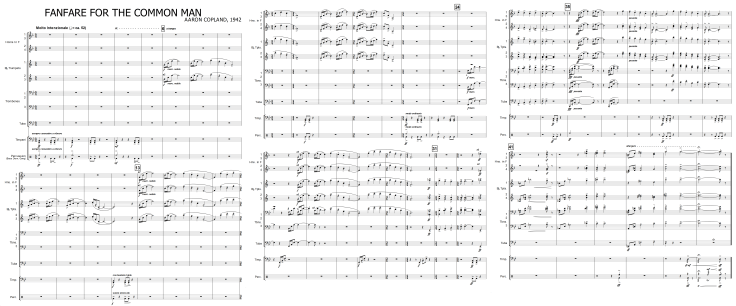

ANALYSIS – COPELAND, AARON (1942) FANFARE FOR THE COMMON MAN

Fanfare for the Common Man [from the Library of Congress]

“Fanfare for the Common Man” was certainly Copland’s best known concert opener. He wrote it in response to a solicitation from Eugene Goosens for a musical tribute honoring those engaged in World War II. Goosens, conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, originally had in mind a fanfare “… for Soldiers, or for Airmen or Sailors” and planned to open his 1942 concert season with it.

Aaron Copland later wrote, “The challenge was to compose a traditional fanfare, direct and powerful, yet with a contemporary sound.” To the ultimate delight of audiences Copland managed to weave musical complexity with popular style. He worked slowly and deliberately, however, and the piece was not ready until a full month after the proposed premier.

To Goosens’ surprise Copland titled the piece “Fanfare for the Common Man” (although his sketches show he also experimented with other titles such as “Fanfare for a Solemn Ceremony” and “Fanfare for Four Freedoms”). Fortunately Goosens loved the work, despite his puzzlement over the title, and decided with Copland to preview it on March 12, 1943. As income taxes were to be paid on March 15 that year, they both felt it was an opportune moment to honor the common man. Copland later wrote, “Since that occasion, ‘Fanfare’ has been played by many and varied ensembles, ranging from the U.S. Air Force Band to the popular Emerson, Lake, and Palmer group … I confess that I prefer ‘Fanfare’ in the original version, and I later used it in the final movement of my Third Symphony.”

Aaron Copland, said the composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, was the one to “lead American music out of the wilderness.” Copland’s musical opus, for which he received the 1964 Medal of Freedom, also included such masterworks as “Piano Variations” (1930), “El Salon Mexico” (1936), “Billy the Kid” (1938), “Fanfare for the Common Man” (1942), “Rodeo” (1942), “Appalachian Spring” (1944), and “Inscape” (1967).

Library of Congress (2002) “Fanfare for the Common Man” http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/loc.natlib.ihas.200000006/default.html

accessed on 24 February 2013.

Aaron Copeland invented a unique musical language to capture the ideal of the common man, and man against nature. The Common Man comes from the American philosophy of Rugged Individualism. The common man is celebrated for his commonness, his heartiness, his bravery and wits, his Intuition. He is content on his own, surviving in the wilderness forging his life in freedom (though perhaps not with freewill).

Section A

The piece opens with the rumbling of timpani (tuneable orchestral kettle drums). What is the function of this first collection of sounds (call it Section A)?

Using musical or scientific terms where you are able, and phenomenological terms where you are not, describe the sonic elements of Section A.

Section B

Following Section A… a Fanfare.

What are we celebrating?

What tells us ‘this is a fanfare’?

The wide-open plains are suggested in the harmony (arpeggiated here). Copeland does not build chords on consecutive thirds, like most western music of the last 400 years. Instead, he builds chords using consecutive 4ths and 5ths, which has qualia distinct from triadic harmony (e.g. G major, D minor).

Attempt to describe the qualia of the harmony.

Section C

Musically speaking, what has change here from Section B?

Section D

Describe the texture and its qualia in Section D

Does this piece have any meaning to you? Support your answer, even if your response is “it doesn’t mean anything to me”.

SEE ASSIGNMENT: COMPOSE THREE SHORT FANFARES